Summary

In the vast landscape of the internet, knowledge is power. For security professionals, understanding the intricacies of a target's digital presence is paramount. This is where web reconnaissance comes into play – the art and science of gathering information about websites and web applications.

This module provides a comprehensive guide to the essential skill of web reconnaissance. Key areas covered include:

WHOIS: Understand WHOIS and its role in reconnaissance.DNS: Understanding the Domain Name System and its role in reconnaissance.Subdomains: Techniques for discovering and analyzing subdomains.Web Crawling: Automated exploration of websites for information gathering.Web Archives: Utilizing the Wayback Machine to access historical website data.Search Engine Discovery: Leveraging search engines for reconnaissance and open-source intelligence gathering.Fingerprinting: Identifying the technologies powering a website or web application.

This module is broken into sections with accompanying hands-on exercises to practice each of the tactics and techniques we cover.

As you work through the module, you will see example commands and command output for the various topics introduced. It is worth reproducing as many of these examples as possible to reinforce further the concepts presented in each section. You can do this in the target host provided in the interactive sections or your virtual machine.

You can start and stop the module at any time and pick up where you left off. There is no time limit or "grading," but you must complete all of the exercises and the skills assessment to receive the maximum number of cubes and have this module marked as complete in any paths you have chosen.

The module is classified as "Easy" but assumes a working knowledge of the Linux command line and an understanding of information security fundamentals.

A firm grasp of the following modules can be considered prerequisites for successful completion of this module:

- Linux Fundamentals

- Web Requests

- Introduction to Web Applications

Introduction

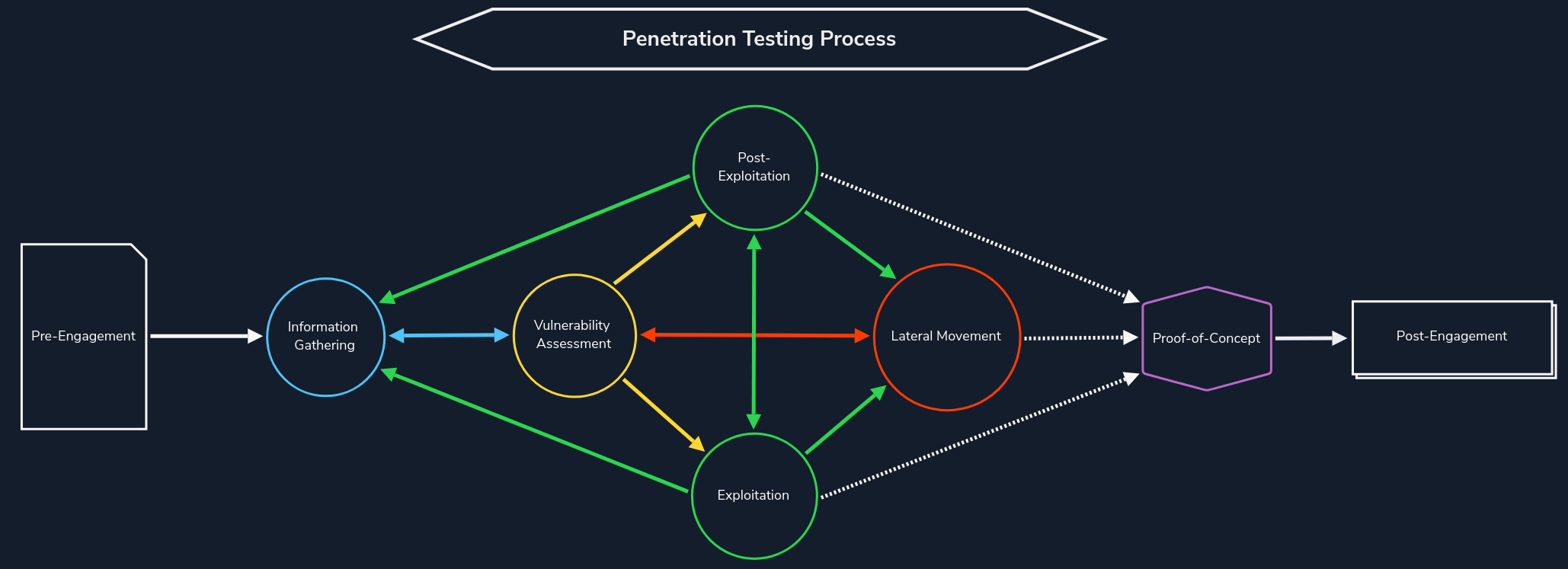

Web Reconnaissance is the foundation of a thorough security assessment. This process involves systematically and meticulously collecting information about a target website or web application. Think of it as the preparatory phase before delving into deeper analysis and potential exploitation. It forms a critical part of the "Information Gathering" phase of the Penetration Testing Process.

The primary goals of web reconnaissance include:

Identifying Assets: Uncovering all publicly accessible components of the target, such as web pages, subdomains, IP addresses, and technologies used. This step provides a comprehensive overview of the target's online presence.Discovering Hidden Information: Locating sensitive information that might be inadvertently exposed, including backup files, configuration files, or internal documentation. These findings can reveal valuable insights and potential entry points for attacks.Analysing the Attack Surface: Examining the target's attack surface to identify potential vulnerabilities and weaknesses. This involves assessing the technologies used, configurations, and possible entry points for exploitation.Gathering Intelligence: Collecting information that can be leveraged for further exploitation or social engineering attacks. This includes identifying key personnel, email addresses, or patterns of behaviour that could be exploited.

Attackers leverage this information to tailor their attacks, allowing them to target specific weaknesses and bypass security measures. Conversely, defenders use recon to proactively identify and patch vulnerabilities before malicious actors can leverage them.

Types of Reconnaissance

Web reconnaissance encompasses two fundamental methodologies: active and passive reconnaissance. Each approach offers distinct advantages and challenges, and understanding their differences is crucial for adequate information gathering.

Active Reconnaissance

In active reconnaissance, the attacker directly interacts with the target system to gather information. This interaction can take various forms:

| Technique | Description | Example | Tools | Risk of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Port Scanning |

Identifying open ports and services running on the target. | Using Nmap to scan a web server for open ports like 80 (HTTP) and 443 (HTTPS). | Nmap, Masscan, Unicornscan | High: Direct interaction with the target can trigger intrusion detection systems (IDS) and firewalls. |

Vulnerability Scanning |

Probing the target for known vulnerabilities, such as outdated software or misconfigurations. | Running Nessus against a web application to check for SQL injection flaws or cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities. | Nessus, OpenVAS, Nikto | High: Vulnerability scanners send exploit payloads that security solutions can detect. |

Network Mapping |

Mapping the target's network topology, including connected devices and their relationships. | Using traceroute to determine the path packets take to reach the target server, revealing potential network hops and infrastructure. | Traceroute, Nmap | Medium to High: Excessive or unusual network traffic can raise suspicion. |

Banner Grabbing |

Retrieving information from banners displayed by services running on the target. | Connecting to a web server on port 80 and examining the HTTP banner to identify the web server software and version. | Netcat, curl | Low: Banner grabbing typically involves minimal interaction but can still be logged. |

OS Fingerprinting |

Identifying the operating system running on the target. | Using Nmap's OS detection capabilities (-O) to determine if the target is running Windows, Linux, or another OS. |

Nmap, Xprobe2 | Low: OS fingerprinting is usually passive, but some advanced techniques can be detected. |

Service Enumeration |

Determining the specific versions of services running on open ports. | Using Nmap's service version detection (-sV) to determine if a web server is running Apache 2.4.50 or Nginx 1.18.0. |

Nmap | Low: Similar to banner grabbing, service enumeration can be logged but is less likely to trigger alerts. |

Web Spidering |

Crawling the target website to identify web pages, directories, and files. | Running a web crawler like Burp Suite Spider or OWASP ZAP Spider to map out the structure of a website and discover hidden resources. | Burp Suite Spider, OWASP ZAP Spider, Scrapy (customisable) | Low to Medium: Can be detected if the crawler's behaviour is not carefully configured to mimic legitimate traffic. |

Active reconnaissance provides a direct and often more comprehensive view of the target's infrastructure and security posture. However, it also carries a higher risk of detection, as the interactions with the target can trigger alerts or raise suspicion.

Passive Reconnaissance

In contrast, passive reconnaissance involves gathering information about the target without directly interacting with it. This relies on analysing publicly available information and resources, such as:

| Technique | Description | Example | Tools | Risk of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Search Engine Queries |

Utilising search engines to uncover information about the target, including websites, social media profiles, and news articles. | Searching Google for "[Target Name] employees" to find employee information or social media profiles. |

Google, DuckDuckGo, Bing, and specialised search engines (e.g., Shodan) | Very Low: Search engine queries are normal internet activity and unlikely to trigger alerts. |

WHOIS Lookups |

Querying WHOIS databases to retrieve domain registration details. | Performing a WHOIS lookup on a target domain to find the registrant's name, contact information, and name servers. | whois command-line tool, online WHOIS lookup services | Very Low: WHOIS queries are legitimate and do not raise suspicion. |

DNS |

Analysing DNS records to identify subdomains, mail servers, and other infrastructure. | Using dig to enumerate subdomains of a target domain. |

dig, nslookup, host, dnsenum, fierce, dnsrecon | Very Low: DNS queries are essential for internet browsing and are not typically flagged as suspicious. |

Web Archive Analysis |

Examining historical snapshots of the target's website to identify changes, vulnerabilities, or hidden information. | Using the Wayback Machine to view past versions of a target website to see how it has changed over time. | Wayback Machine | Very Low: Accessing archived versions of websites is a normal activity. |

Social Media Analysis |

Gathering information from social media platforms like LinkedIn, Twitter, or Facebook. | Searching LinkedIn for employees of a target organisation to learn about their roles, responsibilities, and potential social engineering targets. | LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook, specialised OSINT tools | Very Low: Accessing public social media profiles is not considered intrusive. |

Code Repositories |

Analysing publicly accessible code repositories like GitHub for exposed credentials or vulnerabilities. | Searching GitHub for code snippets or repositories related to the target that might contain sensitive information or code vulnerabilities. | GitHub, GitLab | Very Low: Code repositories are meant for public access, and searching them is not suspicious. |

Passive reconnaissance is generally considered stealthier and less likely to trigger alarms than active reconnaissance. However, it may yield less comprehensive information, as it relies on what's already publicly accessible.

In this module, we will delve into the essential tools and techniques used in web reconnaissance, starting with WHOIS. Understanding the WHOIS protocol provides a gateway to accessing vital information about domain registrations, ownership details, and the digital infrastructure of targets. This foundational knowledge sets the stage for more advanced recon methods we'll explore later.