Summary

Incident handling is a clearly defined set of procedures to manage and respond to security incidents in a computer or network environment. This module introduces the overall process of handling security incidents and walks through each stage of the incident handling process. Important key points and implementation details will also be provided regarding all stages of the incident handling process. This module is also aligned with NIST's Computer "Security Incident Handling Guide", as it is one of the most widely used and referenced resources on the matter.

The fundamentals of monitoring and monitoring using SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) solutions, as well as the majority of SOC-related and investigation-related topics, will be covered in separate modules and in a highly hands-on manner. This module focuses solely on the procedural aspect of incident handling, hence the lack of hands-on exercises.

This module is broken into sections and there are no accompanying hands-on exercises as the focus is understanding the different stages of the incident handling process from a handler's perspective.

You can start and stop the module at any time and pick up where you left off. There is no time limit or "grading," but you must complete all of the question assessments to receive the maximum number of cubes and have this module marked as complete in any paths you have chosen.

The module is classified as "Fundamental" but assumes an understanding of information security fundamentals and common attack principles.

A firm grasp of the following module can be considered a prerequisite for successful completion of this module:

- Penetration Testing Process

Incident Handling

Incident Handling Definition & Scope

Incident handling (IH) has become an important part of an organization's defensive capability against cybercrime. While protective measures are constantly being implemented to prevent or reduce the number of security incidents, an incident handling capability is undeniably a necessity for any organization that cannot afford a compromise of its data confidentiality, integrity, or availability. Some organizations choose to implement this capability in-house, while others rely on third-party providers to support them, continuously or when needed. Before we dive into the world of security incidents, let's define some terms and establish a common understanding of them.

An event is an action occurring in a system or network. Examples of events include:

- A user sending an email.

- A mouse click.

- A firewall allowing a connection request.

An incident is an event with a negative consequence. One example of an incident is a system crash. Another example is unauthorized access to sensitive data. Incidents can also occur due to natural disasters, power failures, so on.

There is no single definition of what an IT security incident is, and therefore it varies between organizations. We define an IT security incident as an event with a clear intent to cause harm that is performed against a computer system. Examples of incidents include:

- Data theft.

- Funds theft.

- Unauthorized access to data.

- Installation and use of malware and remote access tools.

Incident handling is a clearly defined set of procedures for managing and responding to security incidents in a computer or network environment.

It is important to note that incident handling is not limited to intrusion incidents alone.

Other types of incidents, such as those caused by malicious insiders, availability issues, and loss of intellectual property, also fall within the scope of incident handling. A comprehensive incident handling plan should address various types of incidents and provide appropriate measures to identify, contain, eradicate, and recover from them to restore normal business operations as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Bear in mind that it may not be immediately clear that an event is an incident until an initial investigation is performed. That being said, there are some suspicious events that should be treated as incidents unless proven otherwise.

Incident Handling's Value & Generic Notes

IT security incidents frequently involve the compromise of personal and business data, and it is therefore crucial to respond quickly and effectively. In some incidents, the impact may be limited to a few devices, while in others, a large part of the environment can be compromised. A great benefit of having an incident handling team (often referred to as an "incident response team") handle events is that a trained workforce will respond systematically, and therefore appropriate actions will be taken. In fact, the objective of such teams is to minimize the theft of information or the disruption of services that the incident is causing. This is achieved by performing investigations and remediation steps, which we will discuss more in depth shortly. Overall, the decisions that are made before, during, and after an incident will affect its impact.

Because different incidents will have different impacts on the organization, we need to understand the importance of prioritization. Incidents with greater severity will require immediate attention and resources to be allocated to them, while others rated lower may also require an initial investigation to determine whether they are, in fact, IT security incidents that we are dealing with.

The incident handling team is led by an incident manager. This role is often assigned to a SOC manager, CISO/CIO, or third-party (trusted) vendor, and this person usually has the ability to direct other business units as well. The incident manager must be able to obtain information or have the mandate to require any employee in the organization to perform an activity in a timely manner, if necessary. The incident manager is the single point of communication who tracks the activities taken during the investigation and their status of completion.

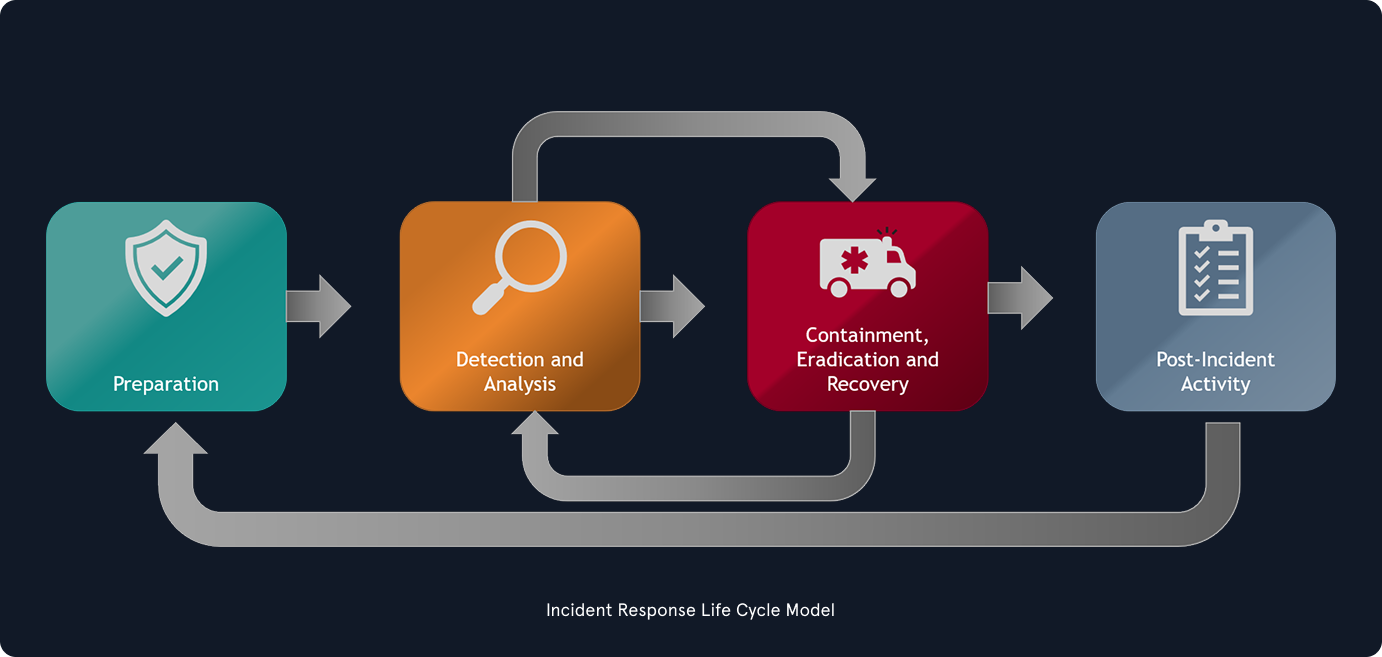

One of the most widely used resources on incident handling is NIST's Computer Security Incident Handling Guide. The document aims to assist organizations in mitigating the risks from computer security incidents by providing practical guidelines for responding to incidents effectively and efficiently.

Different Types of Real-World Incidents

Leaked Credentials

Colonial Pipeline Ransomware Attack: The Colonial Pipeline, a major American oil pipeline system, fell victim to a ransomware attack. This attack originated from a breached employee's personal password, likely found on the dark web, rather than a direct attack on the company's network. The attackers gained access to the company's systems using a compromised password for an inactive VPN (Virtual Private Network) account, which did not have Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) enabled.

Default / Weak Credentials

Mirai Botnet (2016): The Mirai botnet scanned for IoT devices using factory or default credentials (e.g., admin/admin) and conscripted them into a massive DDoS botnet. This led to large-scale DDoS disruptions affecting companies like Dyn and OVH, with hundreds of thousands of devices infected. The root cause was the devices being shipped with unchanged default credentials and poor remote access security.LogicMonitor Incident (2023): Some LogicMonitor customers were compromised because the vendor issued weak default passwords to customer accounts. Affected customers experienced follow-on ransomware incidents or unauthorized access. The root cause involved vendor-assigned weak/default credentials and delayed enforcement of password hardening.

Outdated Software / Unpatched Systems

Equifax (2017) Breach: Attackers exploited a known Apache Struts vulnerability (CVE-2017-5638) in Equifax’s web application. This breach exposed the personal data of approximately 143–147 million people, leading to major regulatory and legal fallout. The incident occurred due to a failure to apply a publicly released patch in a timely manner.WannaCry (2017): The WannaCry ransomware spread as a worm using the SMB EternalBlue exploit, affecting more than 200,000 systems across over 150 countries. High-profile impacts included hospitals and enterprises. This incident was due to unpatched Windows systems, despite the MS17-010 patch being available before the outbreak.

Rogue Employee / Insider Threat

Cash App / Block Inc. (2021 Disclosure; Public 2022 Notice): A former employee accessed the personal information of millions of Cash App users, as reported in company disclosures. Approximately 8.2 million current and former customers were potentially impacted, leading to regulatory scrutiny and settlements. The root cause was the abuse of legitimate employee access and insufficient internal controls and monitoring.

Phishing / Social Engineering

Industry Trend & Representative Data: Phishing is a pervasive vector used to obtain credentials, deliver malware, or trick users into enabling remote access. It frequently leads to account compromise, fraud, and network footholds. A significant portion of breaches over multiple years are linked to phishing.U.S. Interior Department Phishing Attack: Attackers used an "evil twin" technique to trick individuals into connecting to a fake Wi-Fi network, allowing hackers to steal credentials and access the network. This incident revealed a lack of secure wireless network infrastructure and insufficient security measures, including weak user authentication and inadequate network testing.2020 Twitter Account Hijacking: In 2020, many high-profile Twitter accounts were compromised by outside parties to promote a bitcoin scam. Attackers gained access to Twitter's administrative tools, allowing them to alter accounts and post tweets directly. They appeared to have used social engineering to gain access to the tools via Twitter employees.

Supply-Chain Attack

SolarWinds Orion (2020): Nation-state actors compromised the SolarWinds build/release environment and injected a malicious backdoor into Orion updates, which were distributed to thousands of customers. This caused wide-reaching espionage and unauthorized access across government and private sectors, leading to protracted detection and remediation efforts.

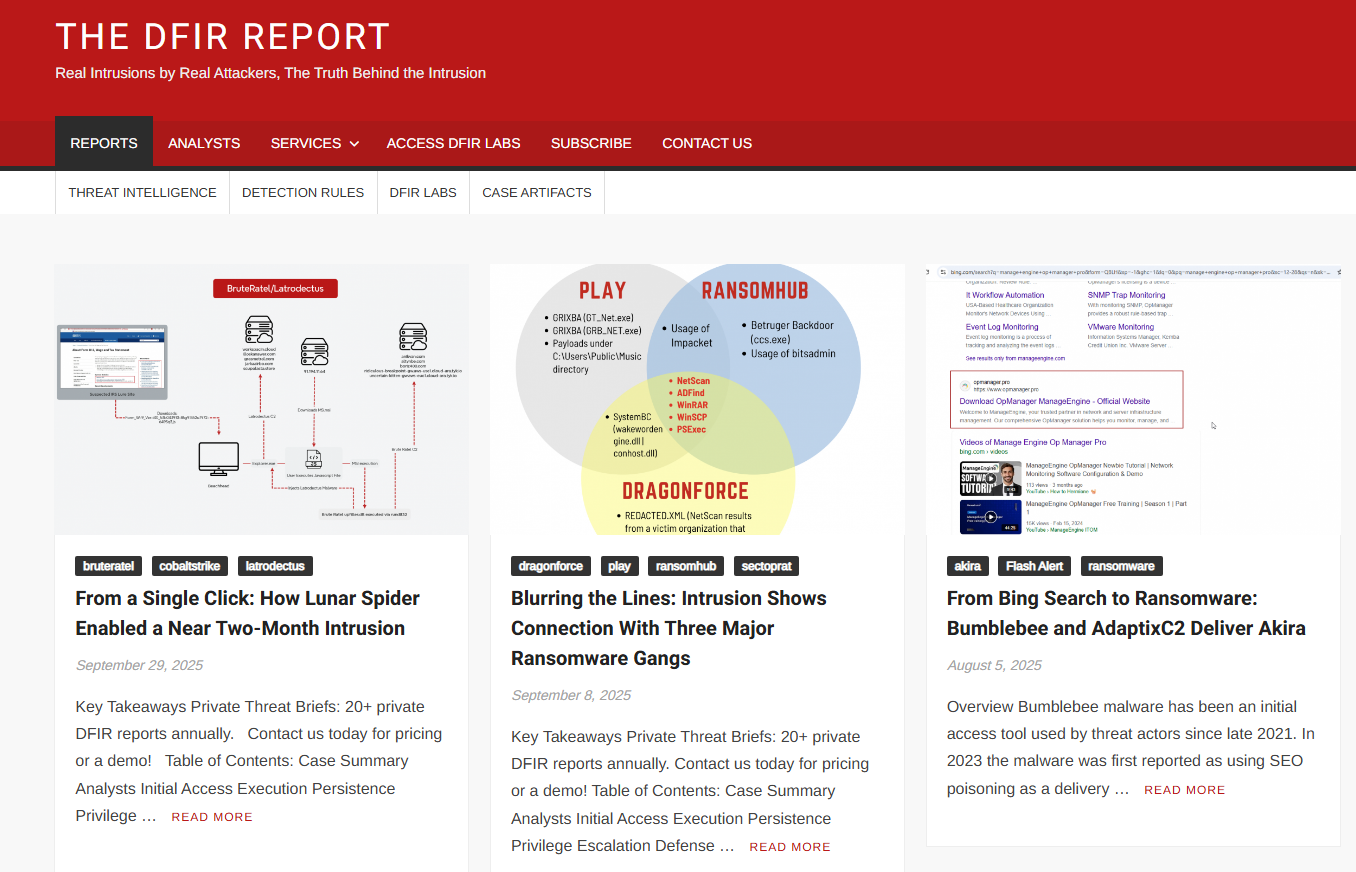

Example of Incident Reports

We should be able to document a real-world security incident in a sequential, stage-by-stage format aligned with frameworks such as the Cyber Kill Chain (explained in the next section) and the MITRE ATT&CK framework (i.e., moving from initial access to impact), just as seen in professional reports from Mandiant, Palo Alto Unit 42, Proofpoint, etc.

An example of an incident report from DFIR Labs is as follows:

This report documents the incident findings in a sequential manner. Each section represents a distinct phase of the adversary’s operation, i.e., from Initial Access and Execution to Exfiltration and Impact. This illustrates how the attack progressed across the environment.

The DFIR Labs platform contains many more incident reports. You can check them out here.

Here's another example of an incident report from Cybereason.

These are incident-specific reports that focus on one particular event or outbreak. For example, the "Confluence Exploit Leads to LockBit Ransomware" style report walks step-by-step through what happened in that one attack: how the adversary gained access, what they did, how they were detected, what the impact was, etc. The aim is to provide a detailed forensic narrative and actionable findings specific to that incident.

There are global incident-response reports as well (such as the 2025 Unit 42 report), which aggregate data from hundreds of incidents across a variety of industries, geographies, and threat actors. Their aim is to identify trends, patterns, emerging threats, and to provide statistical insights, and high-level recommendations for defenders.

For example, the 2025 Unit 42 report states:

- "

In 2024, 86% of incidents that Unit 42 responded to involved business disruption — spanning operational downtime, reputational damage, or both". - Additionally, "

Software supply chain and cloud attacks are growing in both frequency and sophistication. In one campaign, attackers scanned more than 230 million unique targets for sensitive information."

A report from PaloAlto Unit42 that covers global incidents is as follows:

Incident Scenario

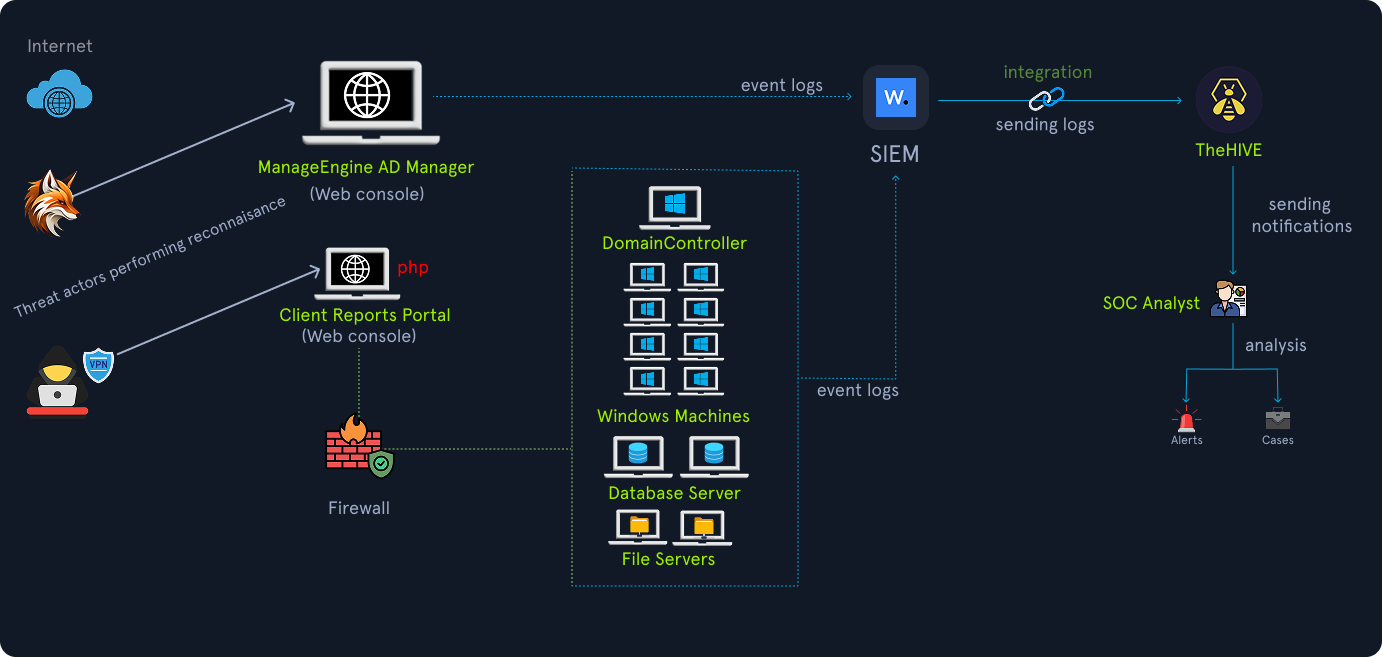

Throughout this module, we'll refer to an incident scenario to understand some challenges that incident handlers face. This incident shows an example of the patterns repeatedly observed in real-world incidents. The victim in this scenario is Insight Nexus, a global market research firm that handles sensitive competitive data for high-profile clients in the IT sector. The firm becomes a target of two distinct threat groups operating simultaneously within its environment.

The diagram below shows an overview of the victim and the threat actors.

Based on the information we have collected, the first threat actor gained entry when system administrators forgot to change the default admin/admin password on an internet-facing application, i.e., ManageEngine ADManager Plus, after a product update. By leveraging this, the attackers logged in successfully, performed reconnaissance, mapped users and machines, and eventually created new privileged Active Directory accounts. Using one of the newly created accounts, the adversaries pivoted further into the environment, identifying an external RDP service exposed by misconfiguration. Exploiting that entry point, they escalated their control and eventually used Group Policy Objects (GPOs) to deploy spyware using an MSI package across multiple endpoints.

In the next section, we'll learn about the Cyber Kill Chain and MITRE ATT&CK frameworks. The phases in these frameworks reflect the attacker's lifecycle and the observable actions at each stage.